Now we can know what a meteoroid – or space rocks – striking Mars sounds like. Thanks to the findings of NASA’s Insight lander. A seismometer was brought to the Red Planet to measure ‘Marsquakes’. The first of these were detected by researchers last year in September, says the US space agency.

This is said to be the very first time that such an impact of a space rock – on another plant – has been recorded. “My surroundings are peaceful and tranquil, allowing me to pick up vibrations from deep inside Mars,” reads a tweet put out from the official handle of the InSight Mission. “But in a first, I’ve also captured seismic waves from a more dramatic source: several meteoroids impacting miles away,” it adds.

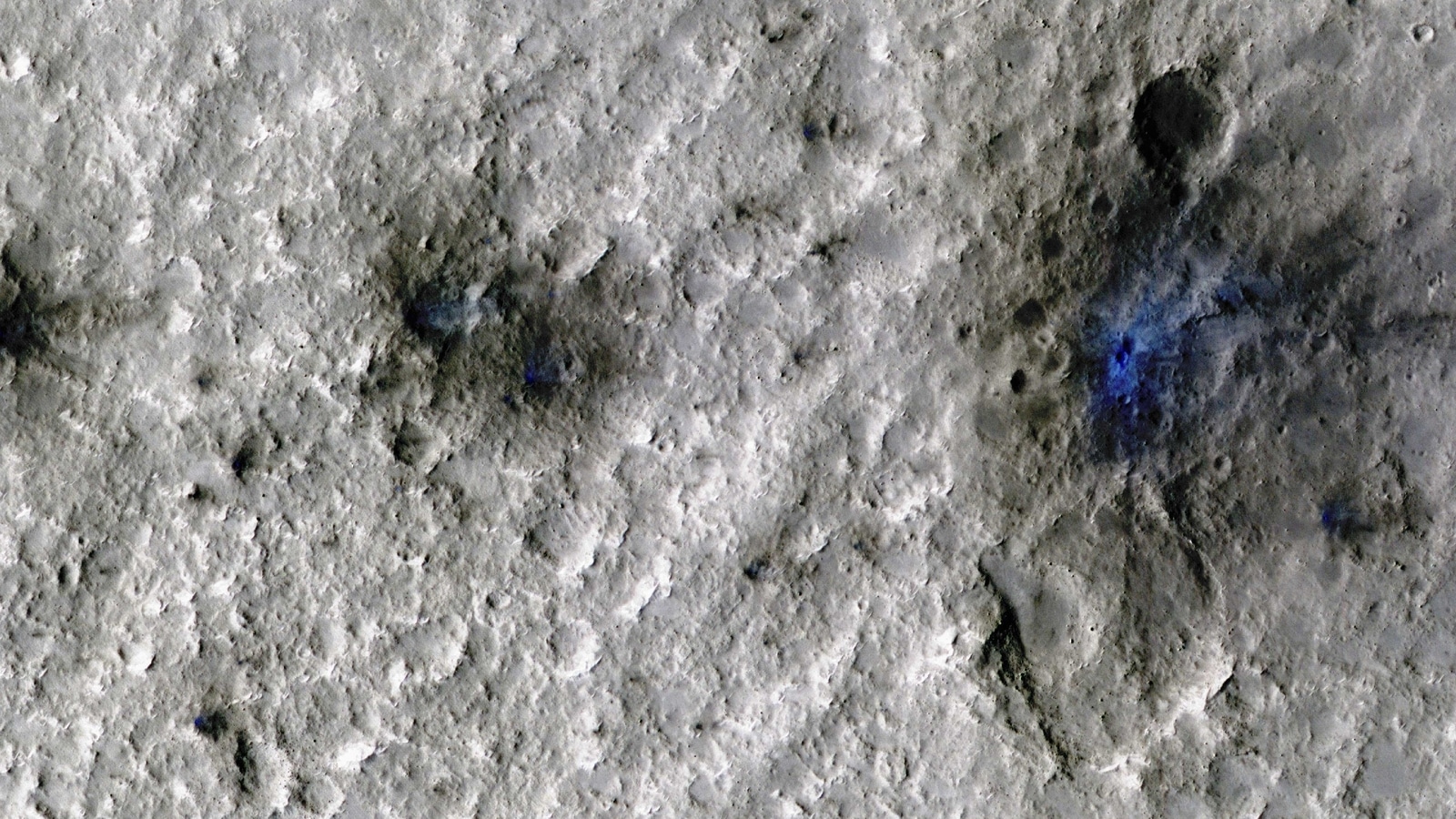

Not just sound, there are visuals too. The Reconnaissance Orbiter’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera has captured at least three craters on the Red Planet. The mission has registered details of impacts of seismic waves – from four space rocks that crashed on Mars in 2020 and 2021 and ranged between 53 and 180 miles (85 and 290 kilometers) – from a region of Mars called Elysium Planitia, the US space agency.

“The first of the four confirmed meteoroids – the term used for space rocks before they hit the ground – made the most dramatic entrance: It entered Mars’ atmosphere on Sept. 5, 2021, exploding into at least three shards that each left a crater behind,” says the space agency.

A Question…

Here’s the next question on researchers’ minds – why they haven’t detected more meteoroid impacts on Mars? “The Red Planet is next to the solar system’s main asteroid belt, which provides an ample supply of space rocks to scar the planet’s surface. Because Mars’ atmosphere is just 1 per cent as thick as Earth’s, more meteoroids pass through it without disintegrating,” NASA said in a statement.

“InSight’s team suspects that other impacts may have been obscured by noise from wind or by seasonal changes in the atmosphere. But now that the distinctive seismic signature of an impact on Mars has been discovered, scientists expect to find more hiding within InSight’s nearly four years of data,” it underlines.