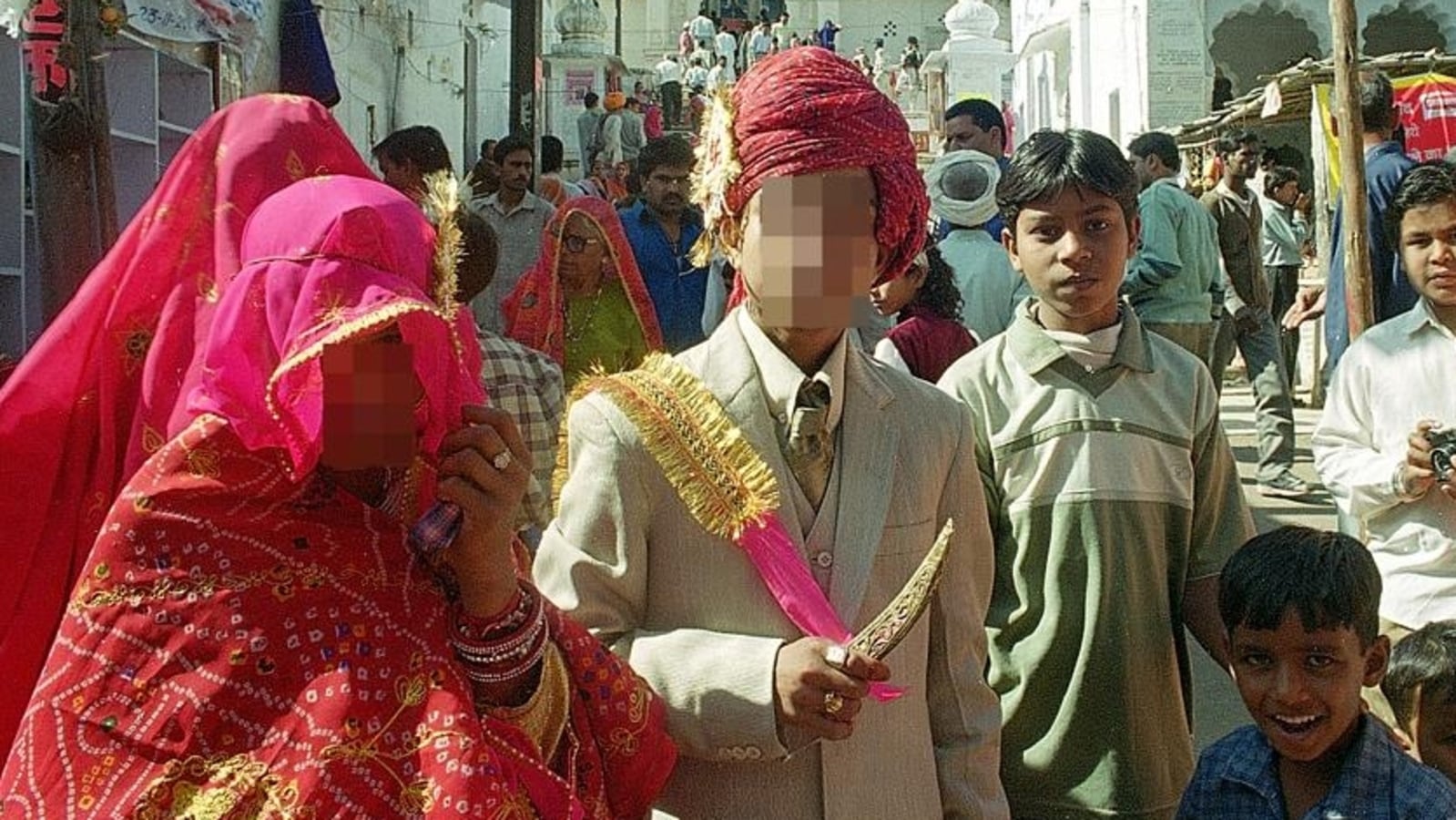

In India, a Parliamentary Standing Committee is currently examining the Prohibition of Child Marriage (Amendment) Bill, 2021, which seeks to raise the legal marriage age for women from 18 to 21.

The Bill has been brought forward on the assumption that raising the legal age will eradicate the practice of child marriage. However, there is little evidence to support this argument, because though the legal age has been set at 18 for several decades, child marriages have continued to take place without any fear of the law. It is therefore not surprising that almost a quarter of women in India reported to have been married before the age of 18, according to the recently released fifth round of the National Family Health Survey—the most comprehensive government survey on health and family welfare.

Child marriage in India, like in many other developing countries, is a consequence of deep-rooted socio-cultural norms. Girls are often raised with the ultimate goal of marriage, confined to the household and not adequately educated or expected to enter the workforce. Until they are married, many families see them as a financial burden and marrying them off early is not only consistent with tradition but also more economically feasible. So, child marriage is often seen as a solution by communities, instead of as a problem.

In the neighbouring country of Bangladesh, findings from a recent research project confirm that a purely legal approach to ending child marriage is not only inefficient but can cause its own negative consequences. In March 2017, the Bangladesh parliament approved a new law to combat child marriage. Among other things, the law significantly increased the penalties (both financial and jail terms) associated with facilitating child marriage. The research project sought to determine how knowledge of the law changed behaviours and attitudes towards child marriage in rural areas of Bangladesh.

The study found that providing individuals with information about a new law did impact individuals’ attitudes and preferences regarding child marriage but in unexpected ways. Both female and male respondents informed about the harsher punishment in the new law were less likely to believe that neighbours and extended family members would approve if parents turned down a marriage proposal for an adolescent daughter. Informing men about the harsher punishments accelerated marriages for adolescent girls within the household—exactly the behaviour that the law was intended to discourage. But the effect was absent when the information was given to just the mothers of adolescent girls. The study confirms that men, especially fathers, continue to make decisions about early marriage for girls, which corresponds to many other studies across the world including India.

The findings demonstrate how a backlash may arise in areas where the legal regime harshly contradicts social norms. Family elders—who occupy the role of the customary authority in rural Bangladesh with regard to marriage—reverted to a more traditional position in response to a legal reform that was too remote from their own preferences and beliefs regarding the appropriate female marriage age. This led to an increase in early marriage pressures within the extended family.

This suggests an immediate parallel—and potential concern—with the proposed Indian law. If a marriage age of 21 for women is viewed as “too remote” from the preferences and norms of many Indian citizens, the law may generate a similar backlash, as customary authorities in rural areas revert to a more traditional position in response to the change in the law.

There are other potential concerns surrounding the proposed bill. If marriage below the age of 21 is made illegal for women, the law may be misused to curtail their autonomy, for example by using the law to punish women who make independent choices about whom and how to marry. More generally, the law would effectively remove the right to marry from millions of adult women, and impose a constraint that could affect many other important life choices—about their education, employment, having children, and so on.

The current socio-economic system makes people want to marry off their daughters as soon as they can or choose not to have a daughter at all. Increasing the legal marriage age without changing patriarchal social norms can result in parents feeling more ‘burdened’ by what they view as additional responsibility of the girl child, which in turn could lead to an increase in sex-selective practices.

Child marriage remains an endemic social problem in India. But to tackle this issue effectively, the Indian government should focus its attention on the real causes of child marriage—deep-rooted gender inequality, regressive social norms, financial insecurity and lack of quality education and employment opportunities for women. Therefore, we need to invest further in girls’ education, in initiatives that empower women economically, and in social and behaviour change communication aimed at changing attitudes towards child marriage in areas where the practice remains entrenched. Addressing the issues directly with such investments is much more likely to lead to positive changes in the lives of men, women and children in India.

The article has been authored by Amrit Amirapu and Zaki Wahhaj, senior lecturer, economics, and reader in economics, University of Kent, Poonam Muttreja, executive director, Population Foundation of India.

![]()